The Origin of Keio's Primary to University Education System

The Origin of Keio's Primary to University Education System

The new concept of a comprehensive education from elementary school to university was devised to foster future leaders of society who would embody the spirit of independence and self-respect. The strength of this concept has been underscored by a history of more than 150 years.

Ware yori inishie wo nasu ("Create history by ourselves")

Keio Gijuku was founded in 1858. That was when Yukichi Fukuzawa, who was enrolled at the Tekijuku School in Osaka at the time, traveled to the Edo residence of the Nakatsu clan under orders from the clan head. As a scholar of Dutch studies, Fukuzawa had the task of teaching his knowledge to the clansmen.

Once in Edo, however, Fukuzawa started to realize that his mission in life was to establish a school. In particular, when he traveled to Europe as a member of the shogun's diplomatic mission in 1862, he investigated the situation in various European countries, and became keenly aware of the need to cultivate character through education.

In 1868, Fukuzawa left the Nakatsu domain residence, bought land and buildings, and moved to Shinsenza in Shiba. It so happened that the Japanese era name at the time was "Keio," and it was from this that Fukuzawa derived the school's name, "Keio Gijuku." The city of Edo was in upheaval due to the Boshin civil war, yet the new school did not close even for one day as the cannons roared on. Fukuzawa's sense of mission grew ever stronger, under the motto Ware yori inishie wo nasu ("Create history by ourselves"). With the confidence borne of maintaining the tradition of western studies in Japan, he would uphold that tradition while opening up a new era.

Keio Gijuku Style - Independence and Freedom, with a Practical Spirit

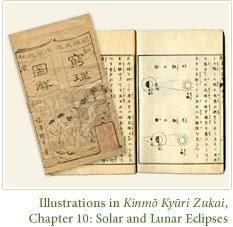

In 1871, Keio Gijuku moved to Mita, and laid the foundations for further development. Fukuzawa wrote and published a number of books at around this time. But it is worth noting that, besides well-known works like Seiyō Jijō ("Things Western") and Gakumon no Susume ("Encouragement of Learning"), he also produced numerous books for children, including Kinmō Kyūri Zukai ("Illustrated Book of Physical Sciences"), Sekai Kunizukushi ("All the Countries of the World"), Keimō Tenarai-no-Fumi ("Book of Reading and Penmanship"), and Dōmō Oshie-Gusa ("Junior Book of Ethics"). In addition he strove to educate families as well. He placed emphasis on education in childhood, as a crucial phase in human growth and development.

At Keio Gijuku, students of different ages were all studying together at first, but a system of education divided by age was gradually developed. In 1868, a children's dormitory was created for junior boarders, and in 1874 Keio Yochisha Elementary School was established. When the university faculties were opened in 1890, the existing courses were renamed the Futsubu School. As time went on, the overlapping of ages between the various schools was eliminated, and in 1898, the current system of primary to university education was established.

At that time, Fukuzawa explained the characteristics of an primary to university education from ages 6 to 22 as follows. "On graduation, these students should not only be superior to other students academically, but should also have absorbed a kind of ethos during their 16 years of rigorous study. That is, in the style of Keio Gijuku ... if we were to dissect this, it would consist of independence and freedom, with a practical spirit." Again, Fukuzawa's autobiography (Fukuō Jiden) includes the famous passage, "If we compare oriental Confucianism with western civilization, we find two things lacking in the Orient: mathematical learning, as the tangible, and a spirit of independence, as the intangible." This statement could be seen to embody "independence and freedom, with a practical spirit".

An unwavering insistence on what is truly important

"Independence and freedom, with a practical spirit" means an independent strength of mind to think thoroughly and practice those thoughts freely, without pandering to or being bound by existing concepts, authority, or temporal trends. And what makes this possible is the ability of scientific thought, with which to carefully observe various phenomena and discern the truth and true principles that lie behind them.

Keio has expected each of its students to foster this kind of spirit, and the school itself has placed great value on this attitude.

We realize the truth of this, in particular, when we consider the history of each of our schools. Keio's education today comprises two elementary schools, three junior high schools, five senior high schools, a university, and graduate schools. Each of these has always continued to ask its students what they think is truly important.

As a result, new initiatives that have been attempted quite out of step with their times have become perfectly normal in later epochs. On many occasions, conversely, we have refused to accept the educational methods prevalent at the time or to be swayed by the latest trends. Even in the 1930s and 40s, when militarism rose to the fore, or in the early postwar period, when the Allied GHQ imposed its will on the land, there were several episodes in which we upheld that resolute attitude toward new trends and the will of those in power.

We think this attitude is particularly important at the stage of primary education, when universal foundations as human beings are laid. For children at that stage, in accordance with their stage of development as human beings, the attitude of never wavering in our quest for what it is truly important, without being swayed by temporal trends or social climate, is of very great significance.